You may have noticed there are a few things I hate about celiac disease. For example, how long it takes doctors to figure us out. The amount of time we spend lost in the logistical maze of insurance claims, referrals, and screwups. The premium we shell out to feel safe, and how long it can take to get better no matter how safe we’re trying to be. I could go on, and I bet you could, too.

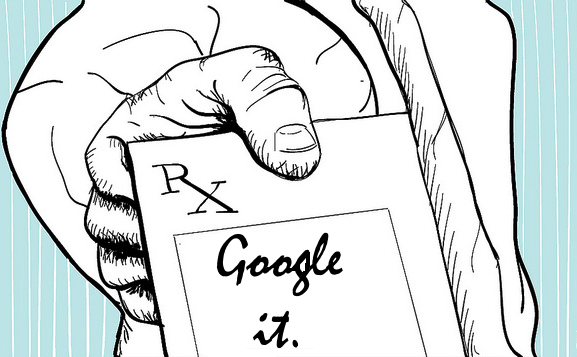

Although there’s plenty of good stuff to say about having this particular disease, with its primarily dietary treatment, during what will no doubt go down in history as the golden age of gluten-free, there’s a lot that could be better. Some doctors’ standard of care for the newly diagnosed still consists of this:

. . . leaving patients unsure where to begin and what, if any, followup care they need. With luck, they stumble across good sources of information, but the less fortunate get mired in muck.

The word “hack” has come to mean finding a clever solution to a tricky problem—and living with celiac disease is definitely that. So, can we hack it? Is there, perhaps, an app for that? In fact, Clay Williams (who I met at the Columbia conference I attended) is about to launch one. It’s called CeliacCare, and Clay was kind enough to answer a few of my burning questions about it.

What is CeliacCare, and why should we be excited about it?

CeliacCare is an application that provides support for the full set of activities someone living with celiac disease needs to undertake to manage the disease and maintain good health. The app helps patients manage the day-to-day aspects of the disease, and ensures they are connected to and supported by their doctors and dietitians.

CeliacCare helps you manage celiac disease through four broad components, which are available on both the mobile app and in the patient portal.

Learn lets you stay abreast of new information about celiac disease and its treatment. This section includes curated material from a variety of celiac disease sources, as well as information that your doctor and dietitian can share with you directly. The information is richly tagged, so you can easily find the latest info on a given topic.

Learn lets you stay abreast of new information about celiac disease and its treatment. This section includes curated material from a variety of celiac disease sources, as well as information that your doctor and dietitian can share with you directly. The information is richly tagged, so you can easily find the latest info on a given topic.

Eat helps you maintain a resource list of favorite things you like to eat, find new gluten-free recipes that are aligned with both your dietary preferences and other sensitivities, and find places to eat out. Our search engine even allows you to locate recipes based on your mood or your desire for a particular food. So, if you’re a bit stressed and you’re craving something crunchy, we can find something yummy for you! We also provide a food diary to help you plan meals and keep track of what you’ve been eating. You may not want to keep a diary all of the time, but making it easy to track things when you need to keep a closer eye on your diet is one of our key goals.

Monitor allows you to keep track of any symptoms you have. Experience has shown that patients who are asked, “How are you feeling?” often answer based on their experience over just the past few days. If you see a doctor or dietitian only once or twice a year, they may not get the whole picture. Tracking and sharing symptoms with a doctor or dietitian will give them a much clearer view of the symptom history of your disease. While the app makes it easy to report a symptom on your own, a particularly novel feature of the app is the ability for a doctor or dietitian to provide special monitoring assistance by running a protocol. When a protocol is run for you, you will automatically receive occasional in-app notifications containing questions or messages from your doctor/dietitian. These assist you in tracking important information that helps them to understand your day-to-day state better.

Care assists in planning visits to your doctor or dietitian. An important aspect of celiac disease management is ensuring you have an ongoing connection with those providing you care. Because your visits may be infrequent, it’s important that you cover everything necessary to maintain good health. Our application automatically provides you a completely personalized agenda for your visit—based on your current disease status, your symptoms, your food diary, and topics that you have added on your own.

CeliacCare is the first app to come out of your company Cohere Health Technologies. Why did you decide to start with celiac disease?

It was the alignment of two different factors. First, I have two friends who have celiac disease, so I’ve seen their challenges firsthand. Second, we had a partner in the recipe space who wanted to address conditions that had a dietary component, and celiac is a good starting point, because gluten is a known culprit. It seemed like the perfect starting point to build capabilities that will both help people with celiac disease and provide a basis to address other dietary issues and sensitivities.

Will CeliacCare also be useful for people with non-celiac gluten sensitivity?

Yes! Features like the sophisticated recipe search, the symptom logging, and the learning areas are broadly applicable. If people with gluten sensitivity are seeing a doctor or dietitian, the care planning feature is also quite helpful.

Some hospitals have systems that allow online communication between patients and doctors (for example, I use Weill Cornell Connect). Do you see CeliacCare as a complement to these systems or a replacement for them?

We are complementary to these systems, and we have designed our platform to make it easy to share information with and receive information from other electronic health technologies. Ultimately, the win for patients is for us to provide novel capabilities that integrate in positive ways with other tools in the healthcare ecosystem.

“Fragmentation” of medical care is annoying. I go to one doctor who says, “You should talk to X doctor about this,” but that doctor says, “It’s more a question for your Y doctor,” who in turn directs me to Dr. Z. Is this app going to help fix that?

This is indeed an annoying issue, and unfortunately isn’t an easy one to solve in a single step. However, Cohere Health is hoping to help with this and other issues of care coordination. The starting point is to get you and all your health-care providers on the same page. Our disease-specific applications are a significant step in this direction. An even more challenging issue is to get doctors who are treating different conditions to coordinate care. A rising percentage of the population is contending with more than one chronic condition. At Cohere Health, we are working to provide an integrated experience when people are using multiple of our applications that are addressing care for different conditions. Through this integration, we will provide a seamless set of capabilities that are personalized to an individual’s specific health challenges.

According to your Cohere site, you plan to “glean useful insights for chronic disease treatment from a variety of health data sources, including [your] apps.” Should people who use CeliacCare have any privacy concerns?

No. Our goal is to build the most patient-friendly application possible, and this means two things. First, CeliacCare is fully HIPAA compliant, meaning your data is encrypted during both transmission and storage, and cannot be shared without your permission. Second, your data belongs to you, meaning that only you decide whether you want it available to medical professionals who might gain insights from it, whether you want to opt out of sharing at any point, or if you want to fully remove it from our system at any time.

When can we get the app? On what devices?

We plan to launch mid-summer on both iOS (Apple) and Android devices. The app will be available in the Apple App Store and on Google Play. You can sign up at www.CeliacCare.com to be notified when it comes out.

Very important: what are your personal favorite gluten-free foods?

I grew up on a farm, and we always had a garden in the summer, so I am a huge fruit and vegetable hound. I like almost every kind of fruit or vegetable, but summertime brings up thoughts of watermelon. When I was about eight years old, my dad was one of the largest growers of watermelon in the nation, and I’ve always thought they tasted like summer. A favorite recipe involving watermelon, cheese, and fresh herbs is available here.

Readers, Clay has some questions for you, too—he’s inviting patients and docs to give feedback to help make the app the best it can be. Check out the website to share your thoughts, and feel free to share a few of them here, too. Do you use any health-related apps already? What clever means have you devised to hack your celiac?

Learn lets you stay abreast of new information about celiac disease and its treatment. This section includes curated material from a variety of celiac disease sources, as well as information that your doctor and dietitian can share with you directly. The information is richly tagged, so you can easily find the latest info on a given topic.

Learn lets you stay abreast of new information about celiac disease and its treatment. This section includes curated material from a variety of celiac disease sources, as well as information that your doctor and dietitian can share with you directly. The information is richly tagged, so you can easily find the latest info on a given topic.

The other pieces might include:

The other pieces might include: